Hazards of Asia’s Highlands and Deserts

Walter Bosshard

“Day in day out we marched towards Ladakh, on the first stage of our journey over the desolate mountain ranges into Chinese Turkestan, days alternating with the most glorious sunshine and violent storms, with snow and bitter, hard frost.” (p.13)

.

Summary

Based on private diary notes written down during his travels with the Trinkler Asian Expedition, Walter Bosshard published his book Hazards of Asia’s Highlands & Deserts in 1932, along with photographs taken during these travels. Together with the head of the expedition Dr. E. Trinkler and the geologist Dr. H. de Terra, Bosshard traveled to the Tibetan Highland and the Taklamakan Desert for geographical, geological and archaeological explorations. The year of the journey is not indicated, but as this travel account was published in 1932, the excursion most probably took place a few years before this date.

Bosshard’s travel account focuses on the hardships and mishaps that the expedition had to deal with during their journey. He writes about dangerous roads on steep hillsides that the caravan had to pass with more than 100 animals and servants, cooks and coolies. Many of the animals died because of lack of water and some servants died from diseases. Besides crossing stormy lakes and windy deserts, they also had to deal with suspicious authorities, who limited their access to places of interest and who did not allow them to conduct excavations and take photographs. The authorities in Chinese Turkestan feared that they would steal treasures from their lands or draw maps for the Russians.

.

Detailed account

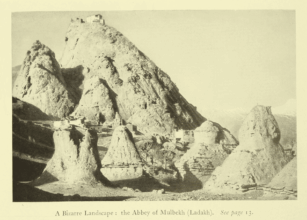

Bosshard’s account starts on the fifth day of the journey, when the expedition is about to leave Srinagar after having moved through the Zogi-la pass on their way to the Indus Valley and Chinese Turkestan. In Ladakh, the expedition reaches the Hemis monastery in a side valley of the Indus, where they encounter pilgrims and merchants heading for the festival of the temple dances. Invited to join the audience, the expedition members are received by the representative of the Dalai-Lama.

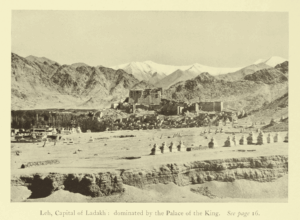

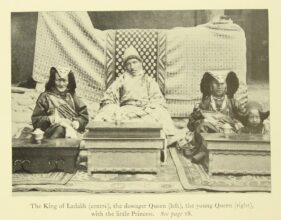

In Leh, the capital of Ladakh, the expedition meets the King of Ladakh, King Tcho-Sykong-Rnam-Rgyal, whose name the author notes as meaning “sole victorious protector of religion” (p.17). A photograph of the King of Ladakh together with his mother, the dowager Queen, and his wife the young Queen and their daughter, can be found next to page 14.

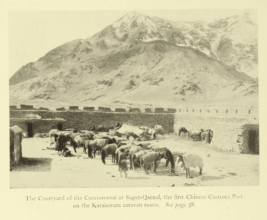

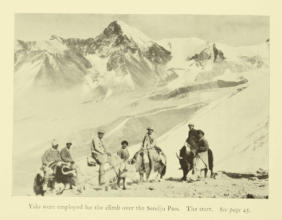

As they continue from Leh, the expedition survives a storm at the Lake of Panggong before moving down into the deep valley of Qara Qash. After two months of walking they reach the Chinese fortress of Suget-Qaraul, where the stationed Amban, the customs-officer, is waiting for them. On rented Kirghiz horses they pass through the Karakorum road, the trade route from India to Central Asia. At Ali-Nazar-Qurghan the caravan faces a tough challenge when the path drastically climbs up the hill and becomes very steep. Leaving the horses behind, they continue on yaks, on a steep and narrow path with animal carcasses lying all over. Finally they reach the top of the Kun-lun mountain chain. At the top, they witness a tragic event when a caravan of pilgrims on their way to Mecca, coming up behind them slip and fall off the hillside never to come back again.

In Yarkand, “the Hermanssons”, a young couple from the Swedish Mission, invite them to stay in their house. From there they continue to Kashgar and Yangi-Hissar where they stay with the Anderssen family. At Hantsheng, which is sometimes called “new Kashgar”, they stay with Mr Toernquist, “the oldest of the Swedish missionaries”. Bosshard notes that “[t]he mission at old Kashgar comprises several dwellings, a hospital and a church” (p.58).

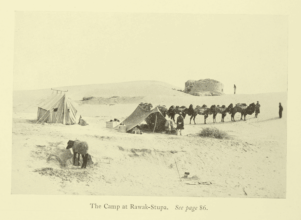

In Khotan, the Afghan Khan Bahadur Badrudhin Sahib receives them in his house, which had been the quarters for visiting Europeans for decades. They proceed through the desert and camp at Rawak-Stupa, which was an important Buddhist temple and a site for pilgrims between the first and seventh centuries, discovered by Sir Aurel Stein. A photograph of their camp at Rawak-Stupa is found next to page 78.

As suspicions against the travelers begin to grow, the Governor of Khotan, the Tao-Tai, receives orders from Urumchi to keep track of the activities of their guests. Bosshard has the following comment about the suspicion against them: “I felt [the Tao-Tai] was mistrustful, and that he was set against me. He suspected that Dr. Trinkler had a great secret, that he had discovered great treasure in the desert with which he intended to disappear, leaving the country by stealth. Nothing was impossible to these Europeans who had maps in which they could read everything.” (p.102)

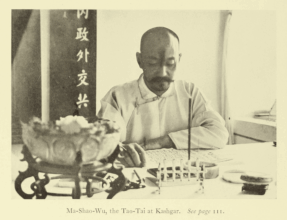

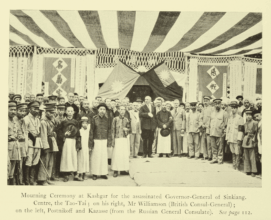

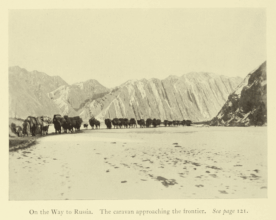

When it is time for him to return to Europe, Bosshard has to wait in Kashgar for several months to get permission to travel back to Europe through Russia. His travel plans are delayed due to the assassination of the Governor-General Yang-Tsen-Hsing in Urumchi, after which the road is said to be unsafe for travelers. A photograph of the mourning ceremony with the Tao-Tai, the British Consul-General Mr. Williamson and Kazasse, the Russian Vice-Consul can be found next to page 110. Finally Bosshard is allowed to leave through Russian Turkestan. A photograph of the caravan approaching the Russian frontier can be found next to page 126.

.

Comments

Two maps can be found on p.56 and p.137, from the Royal Geographical Society:

Map 1: Route taken through Ladakh and over the Karakorum and Kun-lun into Chinese Turkestan, p. 56.

Map 2: The Territory from Kashgar over the Terek Pass to Andijan, Russia, p.137.

.

Azize Güneş