In the Heart of Asia

Percy Thomas Etherton

Summary

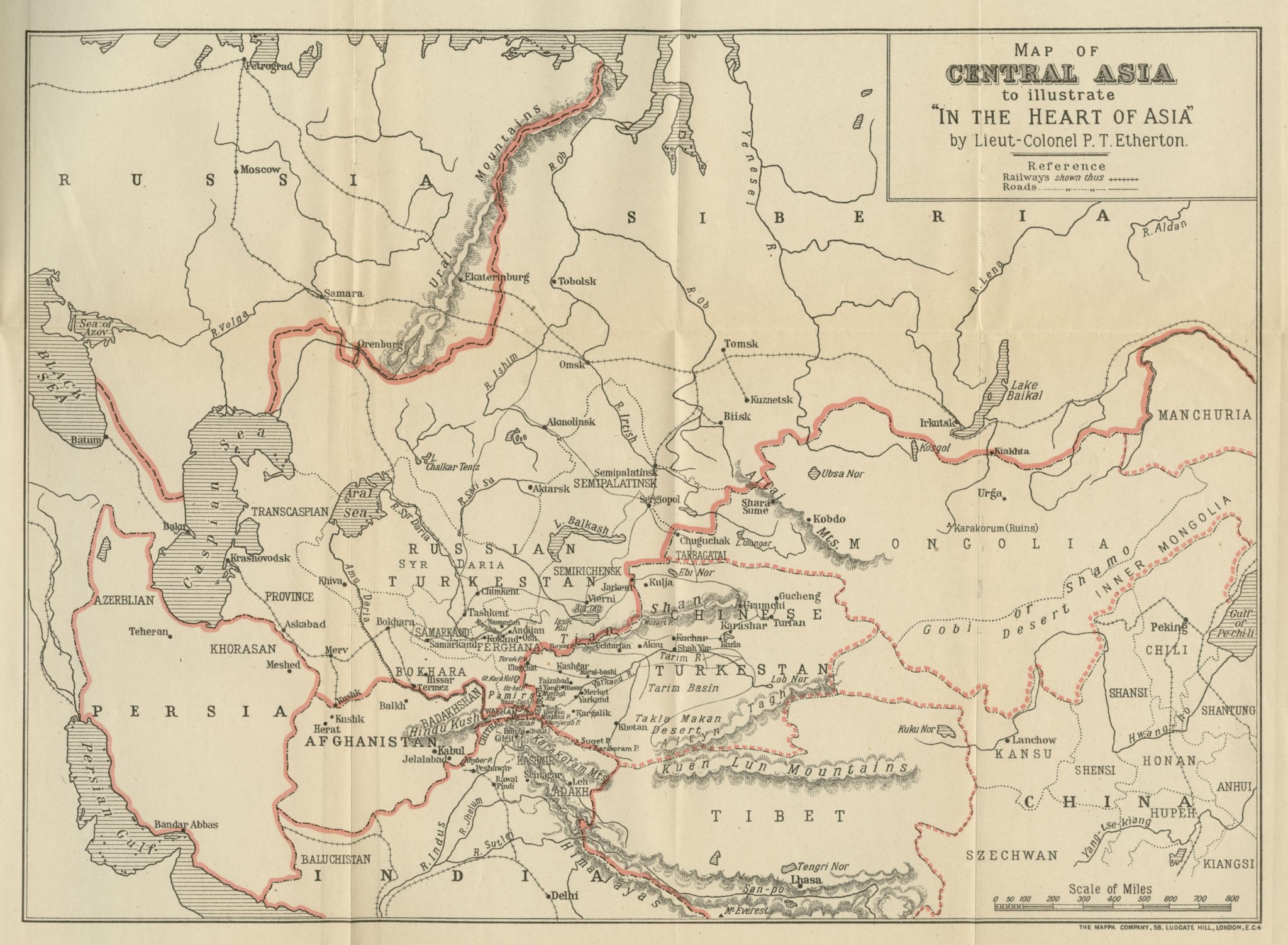

This book is a general account of the economic, commercial and political development in Central Asia and British relations with Russia and China at the beginning of the 20th century, written by Lieut.-Colonel P.T. Etherton, while on duty as the British Consul-General and Political Resident in Chinese Turkistan between 1918 and 1922. Etherton offers a personal narrative rich in details and comments on the tensions between the great powers after World War I and the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 as well as what consequences this might have for Central Asian politics.

The year of 1918 was a point in time when the hegemony of the British Empire in the East was threatened by Bolshevik and German interests in Asia. The risk of the Germans setting up a government in India had recently been eliminated by the outcome of World War I. The end of Czardom caused confusion in Russia and its annexed regions in Asia. At the same time, several regions in Central Asia showed an interest in autonomy, while a movement was on the rise for the creation of a Mohammedan state. Therefore, the author reasoned, it was of vital importance to keep up with a strong British presence between the Caspian Sea and Chinese Turkistan.

.

Detailed account

In connection with his appointment as Consul-General in Kashgar in 1918, Lieut.-Colonel P.T. Etherton joins a secret mission of His Majesty’s Government to “penetrate to Tashkent, the centre of Soviet fanaticism” (pp. 6-7) where a propaganda school is training Bolshevik agitators to spread the message of Bolshevism in all of Asia, especially India, which is a key state in the influence over Asia. The task of the mission is to collect information and report back to the British Empire. The mission starts off from Rawal Pindi and takes a 200 miles long motorway to Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir, which is noted as “the starting-point for Central Asian expeditions” (p. 8). The mission continues to Gilgit and then to Central Asia through the Pamirs. They pass through Balbit, the capital of the mountain state of Hunza, which holds the passes that lead to Pamir and the valley of the Yarkand River in Chinese Turkestan. Etherton gives a description of Hunza and its people called the Kanjutis who are of the Maulai sect of Islam with the spiritual head Aga Khan, who is said to be descendant of Ali, the son-in-law of the prophet Mohammed.

Chapter 2 (pp. 25-42) is devoted to the Pamirs, the western extensions of the Tibetan mountain system, forming the northern boundary of India, also know as “the Roof of the World”. Etherton points out the geopolitical import of the Pamirs, especially for the Russians. With a total area of reportedly 23.000 square miles, the Pamirs are divided in Afghan, Chinese and Russian territory. The people living in the Pamirs are mostly the Kirghiz, the Kara-Kirghiz of the uplands and the Kirghiz-Kasaks of the steppes. In his account of the Kirghiz culture Etherton retells the national myth of forty Kirgiz girls who dipped their fingers in a magic stream by which they become pregnant and gave birth to the Kirghiz people. Etherton adds that the Kirghiz “are a sociable and hospitable race, and whenever met with the reception was cordial and everything they possessed was placed at our disposal” (p. 34). Etherton also mentions that Marco Polo’s description of the Kirghiz is the same as his own, that in 600 years they haven’t changed “in the unchanging East” (p. 38).

Eventually the road leads them to Chinese Turkistan, “a land of oases” (p. 45). Etherton describes Kashgar as the “political hub”, whereas Yarkand is the commercial hub since it is the trade spot for India and other countries (p. 47). He gives a brief account of Kashgar’s history with Yakub Beg’s rise to power in Chinese Turkistan during the 1860’s and the Russian advance resulting in war and chaos. Finally, Imperial China reconquers Turkistan and sets up a colonial government there. In the re-establishment of Chinese authority, Chinese Turkistan was accorded the status of a province, with its administration in the neighboring province of Kansu. After the Chinese revolution in 1912, Chinese Turkistan became a separate province under the control of a Governor responsible to the Central Government in Peking. Etherton describes the extent of corruption in the province and speculates about its reasons being tied to the vast territory and the taxation system being irregular and unfair.

Etherton has his own, personal reflection on the ethnicities in Chinese Turkistan, which was originally inhabited by Aryan tribes. In the 200’s Mongolian tribes appeared and either drove out the Aryans or mixed with them. Then Arabs came to the area in the 800’s. The majority of the races are of Turkish origin, divided into urban and nomad peoples. The urban peoples are Chinese, Tungans and Turkis, who, he notes, are a mixture of the Tajiks and Usbegs. The nomads are the Kirghiz, Kalmuks, Kazaks, Tajiks and the Mongols. Etherton often expresses himself as being concerned for the wellbeing and development of the peoples in Asia, motivating the presence of British presence in Asia. He makes this remark about the intelligence of the Turkis: “With regard to education, there is a general lack of secular instruction throughout the country. Even in more flourishing times the Turkis were never remarkable for intelligence. The various countries of Asia, such as Arabia, Persia, and India, have produced warriors, poets, and savants, and even from among the nomad Mongols great conquerors have arisen leaving undying fame, but nothing intellectual has emanated from Chinese Turkistan, on whose people is settled an ignorance and a want of everything ideal. The Kashgaris, and the people generally, show no tendency towards advancement and they rest content in their present condition, evincing no desire to improve it” (p. 77). On p. 78, Etherton mentions the schools of the Swedish missionary stations in Kashgar, Yangi Hissar and Yarkand as the only places of foreign education in Kashgaria except for a Turkish school that was opened in Kashgar in 1915, to encourage Pan-Islamic ideas and to promote the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the spiritual leader.

When the secret mission arrives in Kashgar on June 7, 1918, Etherton takes over as Consul-General and Political Resident from Sir George Macartney in Kashgar. The secret mission continues to Tashkent with Sir George Macartney, leaving Etherton in Kashgar. Etherton finds his duty as Consul-General to be a difficult task, although his presence is appreciated by the Chinese authorities because of the constant threat of the Bolsheviks to take over India. He organizes a secret service to deal with different types of intrigues and conspiracies in the foreign surrounding that he finds himself in. He appoints a consular agent, called Aksakal (‘greybeard’), who gives reports and keeps the consular staff up to date about the local situation.

During the summer of 1918 the Bolsheviks are making preparations for riots and revolutions in Asia. Etherton arranges prohibition of cotton export and passport restrictions to protect Chinese Turkistan and he sets up an arms register in Kashgar to keep track of the number of arms and their owners. Another of Etherton duties is to combat the opium trade. He tries to analyze Russian and Chinese policies concerning this issue and the history of opium trade in Central Asia.

Chapter 7 (pp. 147-171) focuses on the Bolsheviks’ attempts to create revolution in Asia by taking advantage of the advance of national movements. The Bolsheviks had secret negotiations with the revolutionary party in Bokhara, which was considered to be the educational centre of Islam. With the fall of Tsarist rule in Russia and the rise of the Bolsheviks, the Bokharans wanted independence and the Bolsheviks helped them to overthrow the ruling Amir in order to act as the “emancipators of the East” (p. 168). Etherton describes the Bolshevik plan for the “Emancipation of the East” by teaching the basics of communism in Tashkent and training agitators. With the succession of the Amir Amanullah in Afghanistan in 1919, Afghanistan initiates cooperation with the Soviet Union hoping to gain independence from the British Empire.

At the end of the book Etherton discusses the possibilities of restoring peace and order in Russia. He writes about the collective psychology of the Russians from a historical perspective: “As a race, the Russians are docile and obedient, and lack the energy and will power to extricate themselves from difficulties” (pp. 295f.). Etherton characterizes the Bolsheviks as a “terrorist body, with plenary powers” that “has swept away every vestige of liberty, freedom of thought and speech, and moral and material welfare” (p. 296). He predicts that the end is near for the Soviet Union, as they have reached the limits of their resources, and he expects a spiritual rise in Russia against Soviet. As the Bolsheviks have oppressed Christianity and the Church, Etherton deems it likely that they will rise again and create a sense of nationalism. The author also speculates about the future of China. He doubts that Bolshevism will be able to manifest itself in China with all its internal conflicts, since Soviet principles of economy interfere with the Chinese way of private trade.

.

Azize Güneş