Travels and Archaeological Field-Work in Mongolia and Sinkiang: A Diary of the Years 1927-1934

Folke Bergman

Summary

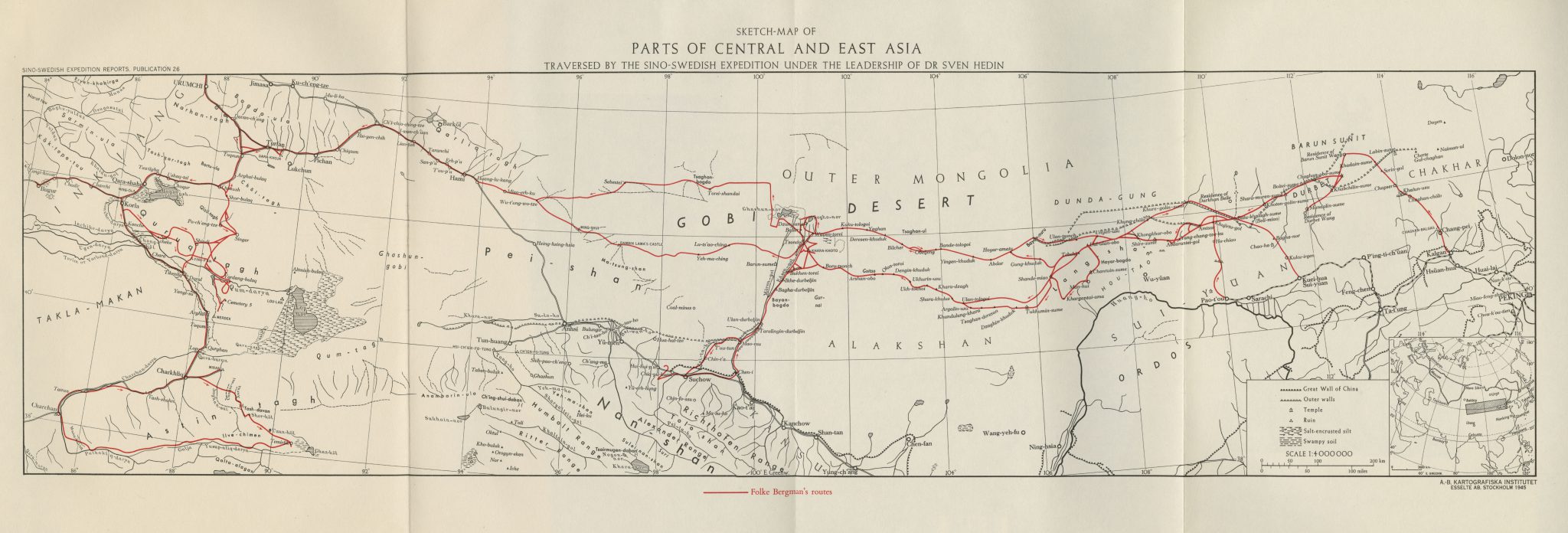

This is a traveler’s journal written by the Swedish archaeologist Folke Bergman about three expeditions to Mongolia and Sinkiang under the leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin, together with a group of Swedish participants consisting of geologist Erik Norin, medico David Hummel and Germans W. Haude, C. Hempel, and H. Dettmann. In February 1927 the expedition arrives in Peking from Moscow on the trans-Siberian railway via Mukden. As a result of archaeological discoveries made by Prof. Johan Gunnar Andersson in Honan, Kansu and Kuku-kor at the beginning of the 1920’s, a prehistory of China was outlined in terms of six successive periods, ranging from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. Especially findings of painted pottery were important in understanding the division of periods. Painted pottery was discovered at sites 4000 km apart. Bergman is excited to further the investigations in Eastern Turkestan to find out more about its role in tying together the Far East and the Near East during the Stone Age. Throughout the journey Bergman gives precise accounts of every place they visit or pass by, noting the time and date of the visits and the distance from the previous place in li – the Chinese measurement where 1 li is about 0,5 km, together with short descriptions of the environment. Black and white photographs and pencil sketches of temples and places are provided throughout the book. On several occasions during its journey the main expedition splits up in order to concentrate on specific research in smaller groups. The expedition is eventually joined by other travelers, such as Nils Ambolt and Henning Haslund-Christensen. A map titled “Sketch-map of Parts of Central and East Asia” is present in the volume with Folke Bergman’s routes marked in red. Bergman conducts excavations and searches for pottery, graves and other artefacts from the Stone Age. At the same time Bergman is also mapping the area and making corrections to Byström’s map (which can be found in an appendix in Hedin’s Southern Tibet). Bergman travels for the most part together with Haslund, who carries out ethnological investigations by conducting anthropometric measurements on Turkis and Mongols.

.

Detailed account

During the first expedition from 1927 to 1929 (pp. 3-86) Bergman and his companions visit places such as the Edsen-gol, Beli-miao, and the valley of Chugungtai-gol. North of Daghain-sume Bergman finds remains of smaller Stone Age sites and graves. They pass and camp at places such as Gechik-khuduk, Tiger Valley, The Boryp Hills, and Chendamen-khara-tologoi. They Camp at Horien-dubche, west of which the Chinese huts at Kharadzagh or Khardjack in the Gobi dessert could be found. Here Bergman spots well-worked Stone Age tools in the middle of the dry and sterile Gobi desert. He speculates that the main “reason why people found their way here during the Stone Age is to seek in the rich supply among the basalt hills of flint-like stones, that are excellently adapted for the making of tools and weapons” (p. 14). The climate of this region was most probably more favorable during the Stone Age.

On their way to Sinkiang Bergman and his companions visit the town Khara-khoto. On the way to Urumchi they visit the Bezeklik grottoes with numerous Buddhistic paintings, and the big ruined town Qara-khoja. After a visit to the village Shindi where they attend a Turki wedding, they enter the Charkhliq district and the small village of Arghan. Bergman notes that “Arghan is important as marking the point where the Yarkend-darya and the Koncha-darya flowed together, and it is given on all maps” (p. 40). Bergman learns that the Yarkend-darya hasn’t carried water for at least 4 years. They continue to Temirlik via Tash-davan (pp. 44-51). In Temirlik Turkis are living in dens, because the Mongols don’t allow them to build proper houses. Outside of Temirlik Haslund accidentally shoots two horses and to sort out this potentially dangerous affair, the nearest Mongol official, a soldier-chief is called to the village. He judges that Haslund meant no harm, but has to pay a fee to the owners of the horses. Afterwards Bergman and his companions visit the soldier-chief in his camp consisting of nine yurts and two tents. Bergman notes that: “The easternmost yurt was a temple and had as a crowning emblem a lamaistic prayer-wheel that was driven by the wind! This construction undeniably bore witness to a certain rationalization of religion, and was a marvellous illustration of the Mongol aversion to work.” (p. 54) In Charchan (pp. 66-67) the Turki villagers approach Bergman with finds they have come across from Kohna-shahr, a huge area to the west consisting of bare gravel desert. One of the few Chinese living there had found a perfectly intact Stone Age vase with painting, which was the first intact painted prehistoric vessel from the whole of Sinkiang. According to Bergman’s estimation the findings from here date back to various periods within the first millennium A. D. and from the first centuries after 1000 A. D. After continuing to the Lop-nor basin, Charkhliq, Tikenliq, Korla and Shindi, Bergman leaves for Sweden after having been away for 2 years.

The second expedition takes place between 1929 and1931 (pp. 87-173). This time the Swedish Government has offered a bigger grant for the continuation of the expedition; as a consequence of this the Swedish participants have increased in number. Bergman leaves Stockholm in April 1929. However, at the Chinese border they have to await permission to enter from the Governor in the nearby town Chuguchaq (Tahcheng). Here they meet the Torgut Princess Nirgidma, who had previously met Hedin and Hummel in Peking. She is on her way to her tribe near Hsi-hu or Khurd-khara-usu. After not being allowed in to China, Bergman and his companions spend some time in Bakhty, a Russian frontier station (pp. 89-91). Once in Mongolia, Bergman decides to make a sketch map of the ruins of Boro-tsonch’s watchtower. There he finds Han coins (Wu-ch’u) and slats with Chinese inscriptions dating back to the Han dynasty. Bergman later continues on to Khara-khoto (pp. 148-151) to examine the relics from the Sung and Yüaneras. Khara-khoto was a center for settlement during the later part of the Sung dynasty and all through the Yüan dynasty. In 1226, Chingghis Khan conquered Khara-khoto and it was in their possession until the end of the Mongol dynasty. A résumé of the archaeological work at the Edsen-gol is given on pp. 153-155.

The third expedition is a motorcar expedition in 1933-1934 to Sinkiang through Mongolia (pp. 174-190). The main goal of the expedition being to explore possibilities of the construction of two highways between China proper and Sinkiang, Bergman is not able to carry out much archaeological work. However, he manages to do some work such as investigating the ruined fort at Ming-shui, positioned halfway between the Edsen-gol and Hami. Bergman writes that the political situation in Sinkiang is bad and that a civil war has been going on since three years. In April and May 1934, Bergman sets out on an archaeological expedition. He has heard from Sven Hedin’s old servant that there exist graves in the desert to the south of the Qum-darya. Bergman eventually finds the burial site and it is called Cemetery 5 in Vol. VII:I, where it is described in great detail. A résumé of the Archaeological Work during the expeditions is given on p. 191.

.

Comments

For an account of the same expedition from astronomer and geodesist Nils Ambolt’s point of view, read Karavan: Travels in Eastern Turkestan (1939).

.

Azize Güneş

Publication

Author: Bergman, Folke

Language: English

Series: Reports from the scientific expedition to the north-western provinces of China under the leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin, the Sino-Swedish expedition, publication: 26: History of the expedition in Asia 1927-1935: 4.

Place: Göteborg

Publisher: Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag

Year: 1945

Pages: 192

Digitized

Appendix:

Sketch-map of Parts of Central and East Asia. Traversed by the Sino-Swedish Expedition under the leadership of Dr Sven Hedin